Programming can be called the art of making immensely big problems smaller and solving them one by one. Programmers divide and conquer entire systems that span across thousands of lines of code, making it all work like a giant clock day by day going full-on with an extremely low chance of an error happening, due to a sophisticated composition of its pieces and thorough testing achieved by experimenting and embracing chaos.

Sometimes, we can have a hard time to pinpoint a small issue that’s going on. If we work with an at least somewhat “old” project, that was maintained not even by one single team, we are like explorers in a jungle - every step is dangerous and we don’t know where to step. Tens of libraries, three frameworks and two synced-up databases your project employs to live up after a decade of development by several teams make it so hard to distinguish a small faulty click in an endless rattling of all the components of your program. There are a bunch of middlewares intercepting your request, then another bunch intercepting the response, some global configurations, sprinkled with a new library you never heard of and some additional services that need to be managed to start and work in the rhythm of the rest of your system.

To solve that, just like every open-source maintainer or a random fellow on StackOverflow will ask you, we can challenge our bugs to a duel we can use a little box where we extract only the thing we need to inspect. Those are called sandboxes, playgrounds, testbeds, reproductions. Just like Storybook allows us to enter the museum of our precious buttons and inspect each and one of them in every possible configuration, a small folder with just a beginner Vite+React template can help us identify why the library is not working as intended, or a composition of different docker-compose configurations can make it seamless to start the service from scratch, without all the overhead a dozen of tables incur when we are just trying to test out this simple stored procedure.

We can make sure that we’re allowed to do whatever the heck we want, be it sudo rm -rf / --no-preserve-root or whatever else. Everything is contained in a box and will never get out, like package.json’s dependencies. We will not just forget to undo this little change that we added to test our existing code, or remove the package that we don’t need, we have no chance of nuking our production database. Since we have this freedom, we are able to experiment beyond what is written in the docs, which promotes better learning with kinesthetic, practical experience we are allowing ourselves to have.

When we have extracted the problem, we erase all possibilities of external unknowns that live in our production system to affect what happens. Instead of relying on abstraction that tells us that some external is running and doing just what it must, instead of delving deep and finding out that it does not, and that it has another dependency that is probably just like itself, we can start anew, with full control over a certain package or a concept that we’re building.

Say, we want to test out the useContext hook works in React. Do we need to use our other, existing projects for that? Surely not. If we learn how to use this hook on itself with a simple example from documentation, then we are ready to use this knowledge for our concrete case. So, we run:

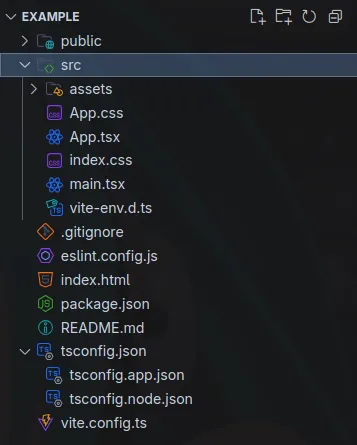

1pnpm create vite@latestchoose React, TypeScript, and here we have a nice clean project:

We can remove all unnecessary things and have a clean white screen, where we would put whatever we need, install dependencies one by one, checking. if we need, whether they have an effect upon each other, trying out a new technology and so on. Being a curious programmer, we add a library, or write some unexpected code and see what happens. We can nuke it completely and start anew, and it makes our journey so much more fun.

For the sake of not setting it up from scratch every time we choose to try something, we can have a separate folder on our machine where all these kind of projects go and live, and then we can have them as either templates to just copy them and add the things we need, or manage everything in one place, adding or removing the dependencies however we see fit.

This, of course does not solve much if we do not actually program and research. But to do anything we need to have a nice environment for substantial work to happen, such as organizing a desk to exclude items that take out attention span. Being aware that it may be better to develop a feature outside of webpack 2-minute compile teams, or being aware that our machine is actually something meant to be broken over and over again, can help us move and tinker and plant and grow the seeds of knowledge that in otherwise strained environments would grow too old or wouldn’t grow at all.

Pet projects are most awesome at that: we start from scratch, and we may start from scratch however much times we want. If something broke, we know why, or we stand closer to the truth, because we know, at least unconsciously, that we placed some piece of malfunctioning code somewhere. Yes, every line of code was placed by someone, and every error that we encounter has its logical source of why it happened, but when you hadn’t checked all these little libraries by yourself, you really cannot be sure of the lack of surprises.

Practicality

For web development, we can have, for example, just a simple index.html + index.js files to try out Vanilla JS things, plus to that we can add a simple Node project with index.js and package.json to try out the JS quirks easily in our terminal. For other fields, we can add something we need day-to-day, to test out the new feature in Java version 777, or to follow a quick tutorial on how to make pagination work with postgresql.

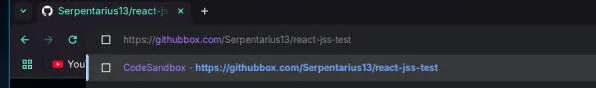

To easily share our code and environment with others, there are projects dedicated to this, for example codesandbox. You can use their “import project button”, but, say, we want to quickly share our GitHub repository with someone so they could tinker with the bug we found. We can go to our repo’s page, and just add a box at the end of domain name:

To share our HTML and CSS without running a whole container somewhere in the cloud, we can use codepen. Although Python is not directly runnable in the browser, we can do it here. Go, C, Rust playgrounds are all available thanks to many people making these projects that help us run the code remotely. Surely, it is possible to install the packages and run all these, having much more control, but if you’re restrained in time or don’t want to clog your system just to check something, they are perfect.

For all kinds of database’s shenanigans, db-fiddle can help out. We are able to fill CREATE TABLE queries alongside something we are stuck with, making the issue as small as possible, to later add the link to it in our dbastackexchange post. This way, people will be able to empirically figure out what’s wrong, instead of trying to interpret your situation the correct way. Oftentimes, when trying to reproduce issue in such an environment, you figure out not so long after starting where you have made a mistake and fix it on your own.

Trying to ensure our website’s functionality, we can setup playwright for it to run an emulated version of multiple browsers to check our project works well in them. If we don’t have a Mac, we can still use Safari through one of the many websites that run their instances and display previews, although slowly, for some cost, or even for free. If we don’t have a phone, we can either setup our Android Studio, running an emulated android, or use a website that emulates IOS, since it is impossible to do on Linux, due to proprietary nature of MacOS and XCode.

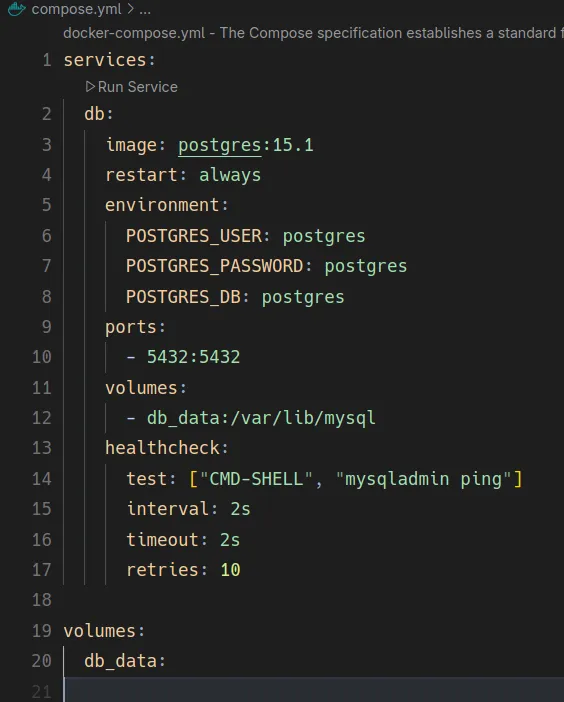

To go a little bit deeper than that, we can use Docker to emulate the environment completely to our behest: we can configure a clean Linux distribution with only the packages we want, starting from Alpine and to Arch Linux, or specific environments for our technology, like node:22. We can also use a Dockerfile with playwright installed, if we can’t use it on our Arch Linux. Having setup a small compose.yml (docker-compose.yml), we can run the needed services with a simple docker compose up <servicename>, having complete control unlike installing those on our machine, tainted by the bits of our own machine that we may not be able to control fully, or at least we don’t want to change all the time just for this one small thing.

Approaching problems like that, instead of banging our head against the wall with too much paint on it, helps us focus on what’s important, which is one of the most important aspect of our evolved brains.

The world is filled with too much information, too much contradictions, but going one by one, and examining each piece of it slowly, allows us to arrive at a complex conclusion later. When we start blank, we help ourselves and our brain run from chaos by exterminating much of it, and work out just a little bit of order that can help us stand firm on what we know and don’t know.

As every tool we make is an inconvenience and point of failure, and to make it work we need to master all interconnected pieces. If we experiment, we are able to reach the truth that no wise voice can tell us: it is right before us, raw as it is. So, I would propose, look in the eyes of the world, and play!

Thanks for reading!